The Unexpected Implications of NIL

While antitrust cases involving the NCAA remain hung up in the courts, the NIL collectives continue to stockpile money under loose and ambiguous regulations. Imagining a world where there are no limits to what schools can pay their athletes makes some people excited for the new world and others sad at the passing of the old one. The interesting thing is the implications of an unregulated NIL could go in contrary directions depending on how athletes, schools, and fans react to an NIL-dominated world. Here are some examples of how throwing the NIL gates wide open could lead to very different outcomes.

Higher Athlete Turnover vs Lower Athlete Turnover

We’ve already seen the combined effects of NIL and the Transfer Portal accelerate the number of college athletes switching between programs. In an unregulated world, this trend could continue at an even greater rate. Athletes would increasingly seek out the highest bidder every year, with effectively every player becoming a free agent at the end of each season. But there is also a path in the opposite direction. If NCAA restrictions no longer apply, it would free up colleges to treat their players like any employee rather than the student-athletes they once classified as. Without the NCAA to regulate how and when a player can transfer, schools could negotiate the right to transfer as part of their terms. Contracts prevent professional players from becoming free agents every year, and the same could apply to college professionals. Payments could contain retention bonuses, clawback clauses, or non-compete clauses that contractually obligate athletes to stay for multiple years in return for NIL payments. Who’s to say vested options and payments, paid out only when an athlete graduates or gets drafted out of their respective colleges, don’t become the norm as it has in the business world?

Determining factor: The current situation is the result of an environment with only partial regulation. The NCAA controls some parts (e.g. transfer policy) and not others (e.g. NIL funding). If an antitrust action removes all NCAA regulations, will schools step in to protect their investments more aggressively than the current environment allows?

More Competitive vs Less Competitive Teams

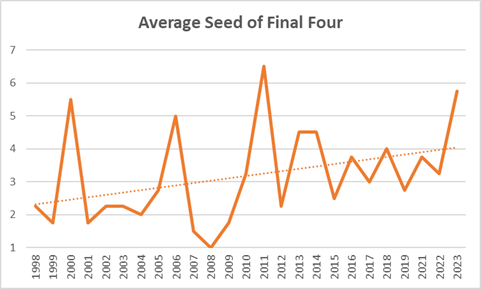

One of the criticisms of the NIL world is that a smaller number of teams will come to dominate the major college sports as only the top programs can amass the NIL war chests required to compete at the very top level. In this scenario, the rich get richer. The contrary argument is that the NIL will democratize the top teams. When the only way college athletes could monetize their career was by playing professionally, established programs with a proven track record of turning out professional players had an insurmountable advantage. A new or unproven program had a disadvantage to high-profile programs that could justifiably argue to recruits that they were a better path to a payday. But for athletes looking to monetize their careers in college, a bigger check could beat a longer tradition. There are schools with large or wealthy alumni bases that can now buy their way into the top echelon.

Determining Factor: How well and quickly can less-established programs monetize the base of supporters will determine whether NIL hurts or helps competition?

The End of the Student-Athlete vs the Return of the Student-Athlete

The old guard is especially critical of the new era in college sports because it effectively cuts the remaining thin thread still connected athletes to their academic institutions. For Division I schools, the athletes could potentially be merely temporary contracted employees with no emotional or academic connection to the school or its student body. Many, though, argue that any connection was only a manufactured illusion anyway, so the current situation is just being more honest about what was a poorly disguised reality meant for the fans.

But consider for a moment that most Division I schools do not make money from their athletic programs. In 2022, only 28 D1 schools had athletic departments whose revenues exceeded their expenses. What might happen when these money-losing schools look at the costs of adding NIL payments to their budgets? They may opt out. It could make financial sense for these schools to establish a league that is a hybrid of the FCS and Division III model. They could still offer scholarships like FCS teams do. And they could still comply with NCAA rules making NIL available to their athletes. It would be a third-party NIL similar to what the D3 schools participate in, where students have to hustle to get real brands to back them. What the top D1 schools are doing is first-party NIL (“collectives”) where the schools are effectively paying the athletes directly from funds they set up themselves. Athletes who benefit from first-party NIL don’t have to find brands or sponsors or do much off the field besides cash the checks. Under this breakout scenario, the D1 FBS league would be reduced to about 30 teams who can afford to pay millions in first-party NIL. Would people still watch and attend games outside this limited FBS universe? The Army-Navy game is an indication that they might, as that game draws a disproportionate audience because it not only celebrates the service of our military but also the true student-athletes that represent them on the field.

Determining Factors: Will the majority of teams that don’t benefit from first-party NIL have the courage and cohesion to pursue an alternate model, and if they do, is there a paying audience that would prefer student-athletes over semi-pro teams?

What these competing scenarios show is that the full implications of an NIL universe are not completely understood or predictable. There are a lot of variables yet to play out. Many people assume college sports are too big to fail and that the trajectory can only be upward. It might be helpful to remember horse racing was the most attended sport in the 1950s and that NASCAR was on its way to becoming the most-watched sport in the 1990s. Not every development is a true step forward.